“The only free road, the Underground Railroad, is owned and managed by the Vigilant Committee. They have tunneled under the whole breadth of the land.” — Henry David Thoreau

February is called “Black History Month,” but in typical leftist fashion Democrats often celebrate corrupt individuals like Marxist Malcolm X and Barack Obama rather than black American heroes like Booker T. Washington and Medgar Evers.

Back in July 2022, I wrote the first article of a series on black American heroes throughout US history, focusing on four individuals from the American Revolution. I highlighted Peter Salem, a “minute man” who witnessed the start of the Revolution at Lexington and Concord and went on to kill British officer Major John Pitcairn at the Battle of Bunker Hill; Salem Poor, whose heroics at Bunker Hill were later recognized in a petition by his fellow soldiers; James Armistead Lafayette, the slave turned Patriot double agent whose spy work was vital in achieving the conclusive American victory at Yorktown; and Phillis Wheatley, the slave who became the first published black American writer and a Revolutionary poetess. Not included in my article, but an underappreciated black hero of the American Revolution, was the slave Cato who became a successful spy for the Revolutionary Army (George Washington’s spy network included multiple black Americans). The second article in my series is long overdue, and today I want to continue with this article celebrating heroes of the Underground Railroad.

The Underground Railroad operated approximately from the late 1700s through the 1850s, up till Abraham Lincoln issued the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation during the Civil War. During that time, tens of thousands of slaves escaped from slave states to free states through the aid of heroic Americans who risked imprisonment and even death to bring enslaved men and women to freedom. Today I am going to highlight just a few of those brave “conductors” and “station masters” on the anti-slavery network called the Underground Railroad.

There are, of course, many white heroes of the Underground Railroad who ensured the slaves could reach freedom. These include John Rankin, a farmer who was the “linchpin” of the Underground Railroad in Ripley, an Ohio town described as a “hotspot” of abolitionist activity. Others were Quaker Isaac Hopper, Quaker “stationmaster” Thomas Garrett, “president of the Underground Railroad” Levi Coffin and his wife Catherine, and Pennsylvania Rep. Thaddeus Stevens. In this article, I am going to focus in more detail on a few black heroes of the Underground Railroad, however.

Elijah Anderson

The Ohio River was a border between slave and free states, often referred to as the “River Jordan” in abolitionist circles (in the Bible, the Israelites entered into the Promised Land by crossing the Jordan River), according to History.com. Ohio river town Madison, Indiana, became an important crossing point for fugitive slaves because of blacksmith Elijah Anderson and other middle-class black citizens of Madison. Anderson, called “General Superintendent” of the Underground Railroad, was black but light-skinned enough that he could fool people into thinking he was actually a white slave owner, which proved very useful when penetrating into slave-owning areas. History.com says, “Anderson took numerous trips into Kentucky, where he purportedly rounded up 20 to 30 enslaved people at a time and whisked them to freedom, sometimes escorting them as far as the Coffins’ home in Newport. The work was exceedingly dangerous. A mob of pro-slavery whites ransacked Madison in 1846 and nearly drowned an Underground Railroad operative, after which Anderson fled upriver to Lawrenceburg, Indiana.” But that didn’t stop Anderson long. He helped no fewer than 800 more fugitive slaves escape to freedom before he was finally caught and imprisoned in Kentucky under the charge of “enticing slaves to run away.” Sadly, Anderson was found dead in suspicious circumstances in his jail cell on the very day in 1861 when he was supposed to be released. This brave man ended up losing his freedom and his life giving life and freedom to hundreds of men and women.

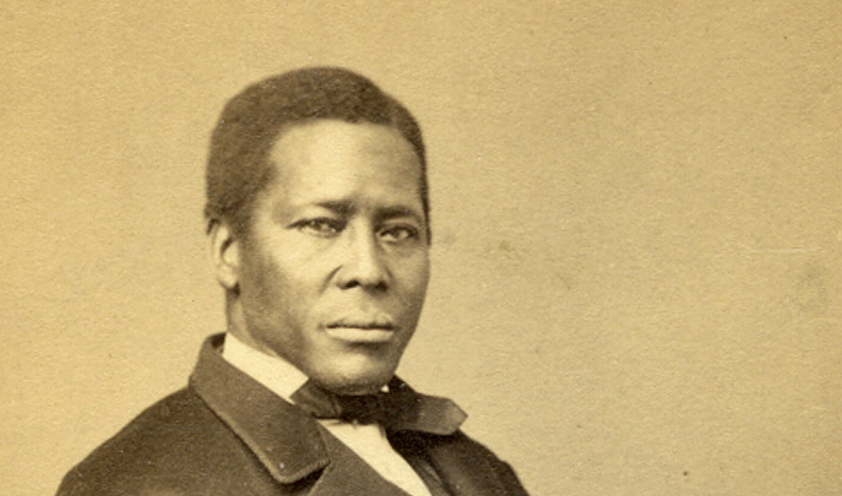

William Still

Wilmington was the last Underground Railroad station in the slave state of Delaware. From there, fugitive slaves went to William Still’s Philadelphia office. Still was a free-born black man, the youngest of 18 children, and the chairman of the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. This society distributed food and clothing to escapees, raised funds, helped coordinate slave escapes, and “served as a one-stop social services shop for hundreds of fugitive slaves each year.”

History.com adds, “Recording the personal histories of his visitors, Still eventually published a book that provided great insight into how the Underground Railroad operated. One arrival to his office turned out to be his long-lost brother [Peter], who had spent decades in bondage in the Deep South. Another time, he assisted Osborne Anderson, the only African-American member of John Brown’s force to survive the Harpers Ferry raid.” Still’s efforts didn’t end with the start of the Civil War, either. “A businessman as well as an abolitionist, Still supplied coal to the Union Army during the Civil War.”

The Smithsonian calls Still the “Forgotten Father of the Underground Railroad” and describes his work in more detail. He was at the center of the dangerous but effective network helping slaves escape to freedom, and his “job was to ensure that fugitives moved through Philadelphia as safely and efficiently as possible.” He coordinated with allies from Philadelphia to Virginia, arranged for fugitives to be met by friendly helpers, provided medical care, food, and even a haircut and bath to fugitive slaves, and raised the money to fund all these works of mercy. Even after the Fugitive Slave Law made hiding fugitives from slave catchers increasingly dangerous even in non-slave states, Still was undeterred. He helped an estimated 1,000 slaves reach freedom through his generous, brave, and persistent work. And Still aided free blacks through other work, too—helping them succeed economically (he saw business as a way for black Americans to conquer the odds), advocating for equal civil rights, including the right to vote, and fighting segregation.

Harriet Tubman

Probably the most famous hero—or rather heroine—of the Underground Railroad is the legendary Harriet Tubman. The Smithsonian said Tubman’s “almost superhuman physical courage enabl[ed] her to travel into the lion’s den to rescue friends and family, all the time facing re-enslavement or worse, and winning her the admiration and fascination of generations since.”

She was impressive not only because of the number of people she brought to freedom and safety, but because all the odds seemed against her escaping identification. She was chased by slave catchers herself when she became a fugitive slave, she soon became famous and had a distinctive scar on her forehead.

She also was illiterate, meaning she had to memorize all intelligence given to her, being unable to read it or write it down. Yet she was never caught. Since Tubman was a woman of deep faith, it has often been said that God miraculously guarded her so that she could be like “Moses” leading her people to freedom.

“Born enslaved on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Harriet Tubman endured constant brutal beatings, one of which involved a two-pound lead weight and left her suffering from seizures and headaches for the rest of her life. Worried that she would be sold and separated from her family, Tubman fled bondage in 1849, following the North Star on a 100-mile trek into Pennsylvania. Nicknamed ‘Moses,’ she went on to become the Underground Railroad’s most famous ‘conductor,’ embarking on about 13 rescue operations back into Maryland and pulling out at least 70 enslaved people, including several siblings. A master of ingenious tricks, such as leaving on Saturdays, two days before slave owners could post runaway notices in the newspapers, she boasted of having never lost a single passenger. Tubman continued her anti-slavery activities during the Civil War, serving as a scout, spy and nurse for the Union Army.”

Tubman reportedly became the first woman to help lead American troops in battle when she partnered with Colonel James Montgomery, an abolitionist and commander of the black regiment the Second South Carolina Volunteers. More precisely, she embarked with Montgomery, his regiment, and some other men, including 50 Rhode Island soldiers, in June 1863 on a river mission.

With Tubman guiding them every step of the way to avoid known torpedoes and to reach their destinations, the soldiers managed to destroy Confederate property including plantations, warehouses, and a pontoon bridge, and to rescue 700 slaves.

The black and white heroes of the Underground Railroad were a bright spot during a dark time in American history. They proved that sometimes upholding true American ideals means violating current American laws, and that selfless sacrifice for freedom makes the noblest American hero.

One Response