➡️ Opinion column written in response to UNTOLD TRUTHS: War Crimes of the Confederates and Post-War Democrats

I was dismayed when I read a recent column by Catherine Salgado entitled “UNTOLD TRUTHS: War Crimes of the Confederates and Post-War Democrats” where she falls for the common post-war liberal consensus about Right vs. Left in light of American history. Truthfully, her assertions are so easily painted as black and white (or more preferably blue and grey), it almost seems too convenient. I would contend that it is.

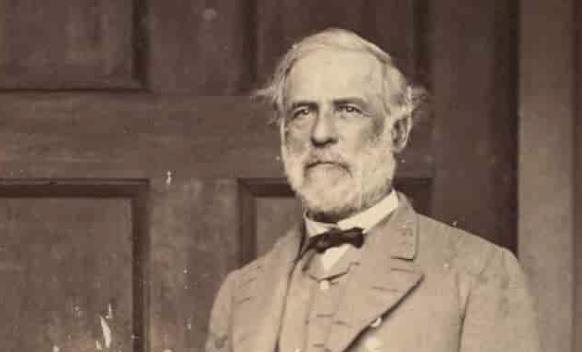

Her understanding of the War Between the States is very modern. She describes the Southern figures of Gen. Robert E. Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis as “traitors” and that “a country that celebrates traitors is setting itself up for failure.”

I agree with Salgado’s assessment that statues and monuments mean something. They reflect a people’s respect and admiration for the things they hold dear. I just disagree with her assessment that the whole lot of the Confederacy were woefully warped sycophants riddled with unrepentant war crimes in the bowels of their collective and individual souls.

She contends that there is history that you’ve never heard before, but I’m uncertain if she intentionally omitted major pieces of history or if she didn’t know, herself.

It must be stated, however, that the historical events Salgado referenced in her column did occur. Those things are true. Heinous acts of violence did occur by the Confederate Army many times directed by the Confederate government. I don’t deny those things, I simply deny the ease with which Salgado makes her argument.

RELATED: UNTOLD TRUTHS: War Crimes of the Confederates and Post-War Democrats

Among some of the major omissions from her column were examples like Confederate Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson who launched a school for his slaves to instruct them in biblical literacy, an act that was likely against Virginia law.

Chris Graham at The American Civil War Museum stated the story of Stonewall Jackson’s school for slaves is insight into “the complexities of interpersonal relationships” during the Antebellum Era.

She omitted the story of Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who Salgado rightly noted became one of the first Grand Wizards of the Ku Klux Klan, who also became a noted speaker at an early NAACP event in Memphis, TN in 1875. Why was that omitted?

Even The New York Times noted Forrest’s speech as “friendly” where he offered reconciliatory language between blacks and whites. The full speech was recorded by The Memphis Daily Appeal.

She omitted the commonly known atrocities committed by Union Gen. William “Tecumseh” Sherman during his burning of Atlanta and his “March to the Sea.” Or how poorly blacks in the Union Army were treated.

However, my purpose in this column is not to conjure up every atrocity that Salgado did not mention. However, it is needed to know that atrocities and other heinous occurrences by Union and Confederate alike do muddy the waters of her point. But now, to my point that they were not, in fact, traitors. This hinges on the idea of the legality of secession.

Lee, arguably the South’s most notable figure, was offered high command of the Union Army upon hearing that militias were being mobilized across the South in 1861. Lee went back and forth on the secession issue, but in the end, he could not bear his sword against his native Virginia.

Many of the common tropes that Salgado and others online have postulated is that the Confederate Army, by raising their sword against the Federal Army, were traitors.

Why, then, did the Union courts not prosecute a single former Confederate for treason after the war? Does Salgado think she is more pious than the United States citizenry and court system of the post-war era?

Lee, Forrest, Davis, and countless other Confederates returned home to their native land and re-swore allegiance to the United States. Every last one of them could have been hanged for their actions, but not of them were.

Clearly, the Union did not view their Southern brothers as traitors. In order to understand this, you have to understand the idea of the formation of the United States in the late 18th century.

The United States, by her own people, was always viewed as a collection of sovereign states compacted, or covenanted, together with the right to come and go from the Union as they pleased.

Each colony-turned-state had their own unique flavor of English-speaking Protestantism. While wildly different, each had a common culture of Anglo-American Christianity that informed their Union, and conversely, their right to leave.

RELATED: Black and White: Little-Known Facts About Race Relations in American History

Rumors of secession were swirling in New England in the 1790s and many northern states were in favor of secession during the War of 1812. John Quincy Adams, arguably the most quintessential “Yankee Republican,” the son of arguably the most quintessential Massachusetts Federalist, even noted as late as 1839 that secession remains a right of a state in “A Solemn Appeal to the People of the Free States.”

The issue was that something palpable shifted in the northern states’ attitude among its political scene towards the issue of secession. What once was the common view of all Americans in the Early Republic period – that secession was a right of the states within the compacted Union – was all of the sudden viewed as an illegal act. Those politicians in the North who perpetuated the idea of an illegal secession drove the South to no choice but to defend their rights as sovereign states to secede.

That said, my own family were Union men. I live in the South now, but my direct lineage consisted of all Northerners who fought for their country. That being said, they came from a part of the Union that sought peace with the South in order to restore the Early Republic, the decentralized, Jeffersonian social order that the United States was founded on.

Southerners, who were concerned over Northern hostility toward the South’s secession movement were vindicated when Lincoln raised federal troops and invaded one of his own states.

Yes, the South fired first at Fort Sumpter, but what is now known as the Deep South, were states that seceded from the Union before the firing upon Fort Sumpter.

My overarching point is this: it’s nonsense to refer to Southerners who fought to defend their farms and families as traitors. Salgado falls for the modern leftist myth that the past was filled by unenlightened barbarians, but “we’re not like that now, we’re so much smarter.”

Just imagine you’re a local farmer in 1863 with a wife and kids living in North Carolina. You hear that there’s an army that’s marching through town burning all farms and homes of your neighbors. I think most sane people would be grabbing a rifle.

There was a phrase used in the years following the Civil War by those who lived through it. It is this: “Before the war, the phrase was ‘The United States are…’ Now it’s ‘The United States is…” A new Constitution and nation was de facto ushered in, in 1865 and the Constitution of a decentralized Jeffersonianism had been put in the grave.

5 Responses

The leaders of the Confederacy were traitors.

The leaders of the Confederacy seceded from the United States and waged war against the federal government. This is a clear violation of the United States Constitution, which prohibits treason.

The leaders of the Confederacy fought to preserve the institution of slavery. Slavery was a fundamental part of the Confederacy, and the leaders of the Confederacy were willing to go to war to protect it.

The leaders of the Confederacy were responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans. The Civil War was the bloodiest war in American history, and the leaders of the Confederacy were responsible for much of the death and destruction.

The idea that the Confederate leader were not traitors is being pushed by supporters of our most modern traitor Donald Trump. Trump became a traitor to the United States because of his actions on January 6, 2021, when a mob of his supporters stormed the United States Capitol Building in an attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. Trump had repeatedly made false claims that the election had been stolen from him, and he encouraged his supporters to march on the Capitol.

After the riot, Trump was impeached by the House of Representatives for inciting an insurrection. He was acquitted by the Republican Senate because they were too intimidated by Trump to do the right thing. Many people believe that he should have been removed from office for his actions.

In addition to the January 6th riot, Trump has also been criticized for his close ties to Russia, his policies towards immigrants, and his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some people believe that his actions have damaged the United States’ reputation on the world stage and have made the country less safe.

Some argue that he was simply exercising his First Amendment rights when he made false claims about the election, and that he did not intend for his supporters to storm the Capitol. This is nonsense. You do not have the right to yell FIRE in a theater and you do not have the right to incite a riot. Trump put the lives of those in the Capitol at high risk -“hang Mile Pence” and his mob.

As of August 9, 2023, there have been over 700 convictions for crimes related to the January 6th attack on the United States Capitol. Of those, over 550 have been sentenced. The longest sentence handed down so far is 14 years in prison.

The following are some of the most common charges that have been brought against the January 6th defendants:

-Obstruction of an official proceeding

-Assaulting, resisting, or impeding officers

-Disorderly or disruptive conduct in a restricted building or grounds

-Entering and remaining in a restricted building or grounds with a deadly or dangerous weapon

-Theft of government property

-Destruction of government property

-Civil disorder

The Department of Justice has said that it expects to bring more charges against January 6th defendants in the coming months and years. Why should Trump be exempt from being called on his actions while his followers sit in prison for his incited riot?

Is there a Civil War history book you recommend?

I just wish that True American History was taught in our schools. But alas that has been resigned to the dust bin of history.

Remember, the “dual” citizens are in charge now, and the US is NOT “Job1″…